Prevent Lettuce from Bolting: 5 Ways to Beat the Bitterness

5 Ways to prevent lettuce from bolting as quickly.

By Steven Biggs

Delay Bitterness and Bolting Lettuce

Once day you're looking at a bed of perfect lettuce plants with juicy, tender leaves. Looks like you have enough lettuce for days.

But before you know it the lettuce heads change shape and start to stretch up in the centre. Your lettuce is bolting.

And with the change in shape comes a change in taste. Bitterness comes with bolting.

But there are ways that you can delay lettuce bolting. This article tells you how.

Bolting Lettuce Plants

It's a normal thing for a lettuce plant to bolt. Lettuce plants start out in leaf-making mode. They make leaves, get bigger, store energy.

But as the lettuce plant gets big enough—and as things around it act as triggers—the lettuce plant changes gears and moves into flowering mode. It bolts.

Lettuce plants are annuals, meaning they have a one-year life cycle. In that one year they flower and make seed.

So your bolting lettuce is a normal thing.

Bolting lettuce plants can get quite tall!

What Bolting Lettuce Looks Like

Bolting lettuce looks a bit like plant yoga as the centre of the leaf rosette begins to stretch upwards. Next, the now-lanky lettuce sends up a flower stalk.

Meanwhile, the leaves become bitter and tough.

What Makes Lettuce Bolt?

Bolting is normal. But lettuce plants don't bolt according to the calendar. A lettuce plant bolts because it's triggered by what's going on around the plant.

Here are triggers:

Heat

Dry conditions

Long days

As you see, lettuce bolts as we get normal summer weather. But you can still enjoy lettuce leaves in the summer using the ideas below.

5 Ways to Delay Lettuce Bolting:

Here are ways to keep growing these cool-season plants during the summer for continuous supply of salad greens:

Choose Slow-to-Bolt Lettuce Varieties

Some lettuce varieties don't bolt as quickly in summer weather. As you're shopping for lettuce seeds, look for a "heat-tolerant" or "bolt-resistant" lettuce variety.

Provide Shade for Summer Lettuce

When conditions are cooler and moister in the spring, lettuce does well in full-sun locations.

But as things heat up, give your lettuce some shade. When it's shadier it's also cooler and there's often more soil moisture.

There are a few ways to grow a shaded lettuce crop in the summer:

Growing lettuce in pots placed in a shady location.

Grow lettuce underneath taller crops that shade it. I grow lettuce underneath staked tomato plants.

Put up a mini hoop tunnel with shade cloth over top of the lettuce.

Grow vining crops such as cucumbers over an A-frame—and grow your lettuce in the shaded space underneath

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Mind the Moisture

Well-watered lettuce doesn't bolt as quickly. Water regularly.

If you're growing in rows and can mulch around plants, a generous layer of mulch helps to hold in moisture.

Don't Overcrowd

Prevent lettuce from bolting quickly with heat-resistant varieties, ample moisture, shade, enough space—and a shock treatment!

Stress can cause lettuce to bolt sooner. When lettuce plants are tightly packed into a garden, there's less space for roots, less space for leaves to grow—and less moisture. These stresses can make lettuce plants bolt sooner.

When I sow a bed of lettuce, I seed fairly densely. But as the little lettuce plants grow, I pull out some of the small plants as I harvest. This allows more space between remaining plants.

Shock Treatment

A little shock can temporarily derail the plant's readiness to bolt. Dig up and transplant a few of your perfect heads of lettuce to give yourself a few extra days of lettuce harvest.

A Non-Bolting Lettuce Alternative

Here's another idea for you: Grow a leafy green that won't bolt.

Swiss chard has a two-year life cycle. It's a "biennial."

That means that for the whole first year, the plant makes leaves. It only bolts in its second year.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Let a Few Lettuce Plants Flower

Lettuce producing seeds that float around the garden if left long enough. Grow your own lettuce seed—and attract birds to the garden with lettuce seed.

When the lettuce begins to bolt, I remove most of the plants. But I keep a few.

Here's why to keep a bolting lettuce plant:

Grow your own seeds. You can save the seeds to plant later, or, you can allow the wind to move the floating seeds around your garden.

Attract finches to the garden. I love to watch gold finches swoop in and land on the tall lettuce seed head to dine on the seeds.

FAQ: Bolting Lettuce

Can you eat bolted lettuce?

It's not toxic, but it's hardly palatable. But if you enjoy something that combines bitter and tough, give it a try.

Can you prevent lettuce from going to seed?

Short of killing the plant, you probably can't derail that one-year life cycle that terminates with seed.

But if you follow the steps above, you can delay bolting and seed formation.

What other leafy greens bolt?

Arugula, spinach, cilantro, bok choy, and mustard are common leafy greens that bolt.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More Vegetable Gardening Ideas

Articles

Courses

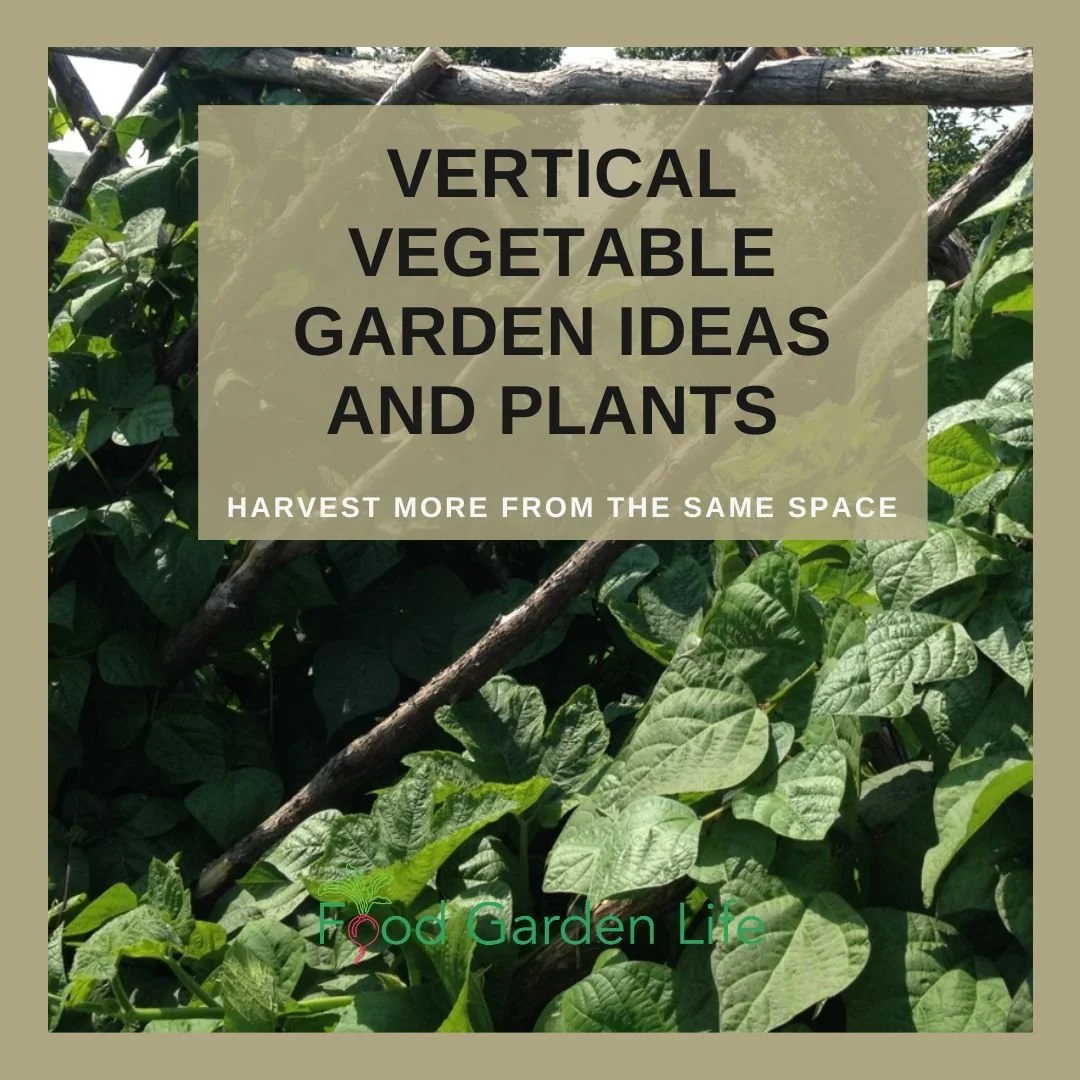

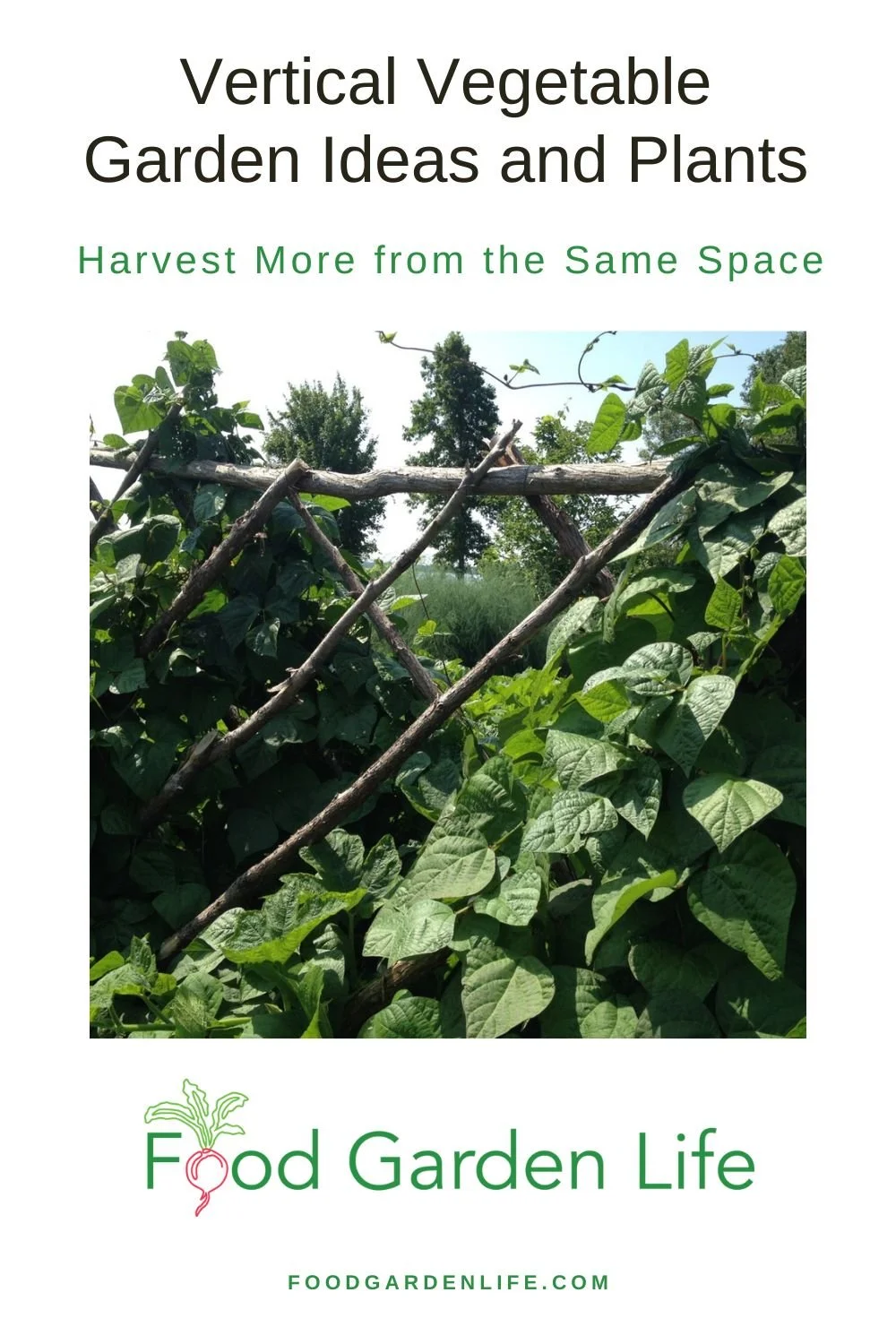

Guide: Vertical Vegetable Garden Ideas and Plants

Harvest more from the same space with these vertical-vegetable-garden ideas and vertical gardening crops.

By Steven Biggs

Vertical Gardens to Harvest More

Vertical vegetable gardening squeezes more plants into a limited space by making use of space above the ground.

By growing sprawling plants upwards, there’s space on the ground to grow more plants.

Other Vertical Garden Benefits

Along with making it possible to grow more plants in the same space, a vertical vegetable garden has a couple of other benefits:

Vertical vegetable gardens for easy harvests. Less bending, because crops are raised

Vertical Gardens Help Provide Shade. Some crops do better in partial shade during the summer. Leafy vegetables grown on the ground space in the shade of a vertical vegetable garden are sheltered from the midday sun.

If you’re interested in creating more growing space to grow vegetables, keep reading. This article includes vertical garden crops, vertical vegetable garden ideas, and easy-to-work-with materials to make supports and trellises.

How to Add Vertical Crops to a Garden

Vertical Vegetable Garden Ideas

There are many ways to add vertical elements to a vegetable garden.

Look for ready-to-use products if you want to start small. It can be something as simple as a tomato cage to support a vining plant—or a window box for cascading herbs.

There are also lots of creative ways to make your own support structures so that you can grow vertically.

Add Tiers with Containers

Containers are a simple way to fit more plants into a garden. Having different tiers means that the canopies of different crops aren’t competing for space at the same level.

Another advantage of containers is that they make it possible to add a crop to an area where there is root competition from a neighbouring crop.

Fences to Support Vines

Squash growing on a fence as part of a vertical vegetable garden.

Fences can be a great opportunity to grow a vertical garden. If the space next to the fence is paved, consider growing in a container.

Tie tomato plants to a chain-link fence

Run twine along a board fence for cucumbers and other vining plants

Grow strawberries or herbs in planters fastened to the fence

Hanging Baskets and Hanging Planters

Vertical gardening doesn’t always mean training a plant upwards.

It can include plants dangling down. A hanging garden.

There are lots of crop options for hanging baskets. Here are ideas to get started:

Add hanging baskets to vertical vegetable gardens.

Strawberries

Tomato plants

Herbs

Salad greens for hanging baskets in partial shade

Trailing nasturtiums (edible flowers!)

Stakes for a Vertical Vegetable Garden

Staked tomatoes leave space for some parsley plants at the ground level.

When staking a plant and growing it upwards you’re opening up space below for another crop. For many gardeners, the sight of staked tomatoes is familiar. Now picture those tomato plants with lettuce or parley underneath.

Some plants can wrap around or grab onto a stake. Other, such as tomatoes, must be tied to the stake.

Self-Supporting Structures for Vertical Gardens

There are many ways to make self-supporting structures for vertical growing.

Even if a vertical garden structure is self-supporting, it’s a good idea to secure it to the ground with a stake so that it doesn’t topple in strong wind.

Here are a few ideas to create vertical space:

Tee Pees

A-frames

A Row of angled, crossing poles jointed together with a pole laying across the top

Grow food vertically using simple bamboo structures such as teepees and A-frames.

Or make more permanent structures for climbing vegetables using lumber:

Lattice-and-lumber A-frame

Wood frames from which twine can be suspended for vining crops

Wooden A-frames over which vining crops grow; and under which shade-tolerant leafy greens thrive during the summer

Or make ornamental landscape features the double as support for growing crops:

Arbours

Pergolas

Use Plants in the Landscape for Vertical Growing Space

Use plants within the landscape to support vining vertical crops:

Save space by growing squash along a hedge!

Hedge (grow a squash vine along a hedge)

Tree (let runner beans grow into a small tree)

Sunflower or corn as a living trellis

Trellises for a Wall Garden

Trellises are a simple way to add more vertical growing space.

Turn an empty wall into a home for a vining crop

Add height to a fence with a trellis

Cover an unsightly utility pole and make it into a growing space

Vertical Garden Crops Ideas

Here are crops that are suited to growing vertically.

Achocha (a.k.a. Bolivian cucumber)

Achocha is a vining crop that’s easy to grow in a vertical vegetable garden.

If you’ve been frustrated by pests and diseases on more delicate vining crops such as cucumber, try achocha. It’s a survivor.

This vining crop has small pods that are eaten raw when small, and cooked when a bit bigger. (There’s a limit to how big they can get without being too woody, so aim to harvest them while small.)

Beans (pole beans and runner beans)

Both of these vining beans are a great addition to a vertical vegetable garden.

Grow them up trellises, garden structures, and tall fences.

Runner beans do better in cooler, maritime climates—and they tolerate partial shade.

Bitter melon

This vining crop has tendrils. Both fruit and young shoot tips are edible. Tolerates partial shade.

Burr Gherkin

Burr gherkin is a vining crop that’s easy to grow in a vertical vegetable garden.

Spiky little cucumber relatives with a citrusy taste. Tasty fresh, and good for pickles too. Vines grow like cucumbers.

Cucamelon

(a.k.a. Mouse Melon, Mexican Sour Gherkin)

This cucumber relative has smaller leaves and fruit, but is a vigorous grow that easily climbs a trellis.

The small, thumbnail-sized fruit are cucumber-like, with a bit of citrus. Eat fresh, or make into pickles.

Cucumbers

Along with conventional cucumbers, look for Armenian cucumbers (not actually a cucumber…but a relative). Both make excellent vining crops.

Luffa

While many people think of using mature luffa fruit for the sponge-like scrubbies, the young luffa is edible—like a summer squash.

If you’re in a cold zone, know that this is a heat-loving crop that does best with a long growing season.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Malabar Spinach

(a.k.a Indian spinach, Ceylon spinach, vine spinach)

This vining plant is a spinach in name only. The leaves are thicker and waxier than true spinach. But it grows all summer—and grows well in heat of summer. The red-leaved varieties are quite ornamental.

Melons

Worried that you can’t grow melons and watermelons vertically because they’re too heavy? Don’t worry. Just make a sling to support the fruit.

Peas

If you've grown bush-types peas, you might not think of them as a vertical vegetable. For vertical gardening, get vining-type peas, which grow 6-8’ tall. ‘Tall Telephone’ is a well-known variety. (Remember, tendrils and shoot tips are edible too!)

Squash

Be sure to grow a vining squash variety, as many of the summer squash have a bush-like growth habit.

And…remember that you can eat more than just the squash fruit. Shoot tips are edible too.

Find out about eating squash tips and other lesser-known edible plant parts.

If you’re growing large winter squash, give extra support with a sling.

Tomatoes

Grow “indeterminate” tomatoes (a.k.a. vining tomatoes) for training upwards. They get taller and taller all summer long.

Most people think of growing tomatoes upwards…but some gardeners also let them dangle down. How about a curtain of tomato vines coming off a low-roofed shed or outbuilding?

Malabar spinach.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Materials for Making DIY Vertical Support Structures

Bamboo Poles

Bamboo poles are an easy-to-use material that is widely available.

Use bamboo poles to stake individual plants, or to make trellises and A-frames.

When attaching poles together to create a trellis or support structure, use twine or zip ties. (Just don’t use the bright yellow zip ties like the ones in the photo below…clear ones are much less noticeable!)

Branches

For a natural look—and for good economy—nothing beats branches.

Twine

Natural-fibre twines such as jute and sisal readily break down when added to the compost pile or buried. They work well for tying plants and for making structures such as teepees.

If the twine will support a lot of weight (e.g. an 8’ high tomato-laden vine by the end of the season) consider something stronger. Either a thicker natural twine, or a synthetic twine.

Lumber

Like branches, lumber can often be scavenged for free.

The one caveat: Don’t use pressure-treated wood. It contains copper compounds.

Lattice

Looking to combine vertical growing with some privacy shields? Lattice could be a building material to consider.

A sheet of lattice usually bends when stood upright, so plan to frame it with wood so that it doesn’t bend.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Metal Stakes

Metal stakes last a long time!

T-bar stakes. Strong. Plan to use a post driver or a sledge hammer to drive them into the ground

Iron rebar. Thinner than T-bars, meaning that if the soil is moist, it can often be pushed into the ground.

PVC Pipe

Use PVC pipe to create supports for your vertical vegetable garden. It's readily available,

Looking for ways to connect horizontal poles to an upright T-bar? Stick a PVC plumbing tee-join on top of the T-bar – and now there are holes on either side into which to slip a horizontal pole.

Wire Mesh

There are a few types of wire mesh available; not all of them at garden centres. See what you can find at hardware and building-supply stores. And if you’re in a rural area, farm-supply stores often carry a good selection of wire.

To get you started as you think about using wire mesh…

Pin this post!

Chicken wire. Easy to cut with tin snips.

Wire mesh to reinforce concrete. (A.k.a. remesh) Not galvanized like some other types of wire mesh, so it quickly takes on the patina of time and blends into the landscape. Tin snips won’t cut through this…plan for bolt cutter or a hack saw.

Hardware cloth. If you want closely spaced mesh that offers a visual shield, this can be an option. Cut with tin snips.

Cattle panels. Often galvanized. The spacing in the lower couple of courses of wire is often less than the other courses. More bendable than the mesh used for concrete—so if you’re looking to make an arch, a better choice.

Rolls of livestock fencing. Various gauges or wire and hole size available.

When buying mesh, think about this:

Do you want a galvanized product or not? Shiny obvious metal, or oxidized and less noticeable?

How will you transport it? Rolls can easily fit into the trunk of a car…but if you’re buying sheets of cattle panel or concrete mesh, you might need to put them on a roof rack (or track down a friend with a pickup truck!)

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More Vegetable Gardening Information

Courses

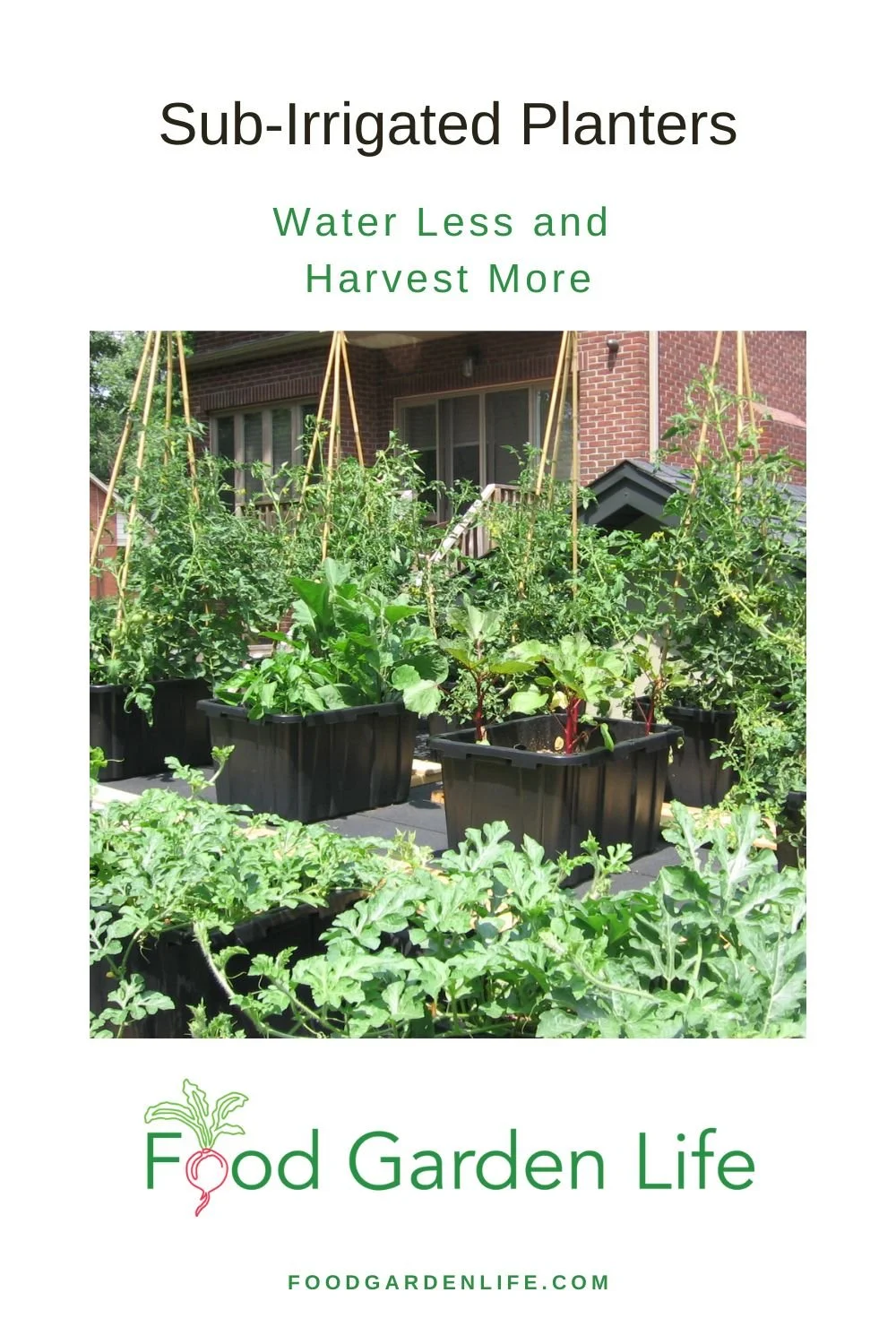

Want to Water Less and Harvest More? Try Sub-Irrigated Planters

Find out how to make your own sub-irrigated planter (a.k.a. self-watering container).

By Steven Biggs

Wilted by Noon

When I first started container gardening on my garage rooftop, I watered every morning. But in the heat of summer, my plants were parched and wilting by noon.

A sub-irrigated planter is an excellent way to solve the problem of parched plants. We want to prevent wilting, because it’s a sign of stress. Drying out is a stress for the crop.

And that stress can delay (or reduce!) your harvest.

Consistent soil moisture is best. Not sopping wet. Not dry.

And that’s where a sub-irrigated planter helps: It keeps the potting mix consistently moist, but not too wet.

This sort of planter is also known as a SIP, a self-watering container, or a self-watering planter.

Keep reading and I’ll explain how a self-watering system works and how you can make your own.

What are Sub-Irrigated Planters?

Sub-irrigation planters are simply planters with a water reservoir at the bottom. The reservoir is right under the soil.

Through capillary action, water wicks up through the potting mix, giving plant roots a consistent supply of moisture. Then, as the plants use water in the soil (creating a moisture gradient) more water wicks upwards from the reservoir.

There are many commercially produced sub-irrigated planters available. Some are fairly basic and resemble a normal container. Others have a gauge that shows the water level in the reservoir.

Self-Watering Planters vs. SIPS vs. Sub-Irrigation Planters

These are all different terms used to describe the same thing: Containers that have a water reservoir below, so that moisture can wick up into the soil.

By the way, they are not truly “self-watering.” The gardener must still fill the reservoir. (If you like do-it-yourself projects, you can automate this with irrigation, see below.)

Benefits of Sub-Irrigated Planters

Pin this post!

First, though, let’s look at the benefits of these self-watering containers.

Less waste:

There is less waste of water and fertilizer because it's a closed system, with less runoff

Higher yield because:

A continuously moist growing medium means the plant has no water stress (plant growth can slow, or flowers drop when the plant is under stress…)

When gardening in a container, the growing medium is warmer than soil in the garden, and that means that harvest begins earlier

Fewer weeds because:

The soil surface is not regularly moistened from overhead watering, giving dry surface conditions are not as good for weed seeds to germinate

The other reason that the soil surface is not as wet is that the farther you are from the reservoir, the less moist the soil (remember, it's going against gravity!)

Less disease because:

With no overhead watering, there's less splashing of disease organisms from the potting soil onto the leaves

And with tomatoes, SIPS usually solve blossom end rot (which actually is not a disease, but a physiological disorder that's caused by swings in soil moisture)

And the benefit of a SIP system that goes without saying: You spend less time spend watering!

Where to Grow in a Sub-Irrigated Planter

I made a garden on my garage rooftop using sub-irrigated (self-watering) planters.

As with any sort of container garden, a SIP makes it possible to grow on patios, decks, driveways.

You can also use them to grow over top of areas with tree roots or compacted soil.

If you’ve been eyeing up a space next to that water-hungry cedar hedge, this is your solution!

If you’re concerned about soil contamination, making a container garden is a simple solution.

Find out more about soil contamination.

What’s Inside a SIP

Here's what you'll usually find in a self-watering planter.

A water-tight area (the reservoir) at the base of the container (underneath the potting mix)

Something to hold the potting mix above the reservoir area: it could be a false bottom such as mesh, or hollow containers, or tubing

A way to add water to the reservoir (a fill-tube that extends above the soil surface)

A wick (the wick is usually the potting mix itself, but a fabric wick can be used too)

An overflow hole, so that if there's too much water, it can escape

How a Sub-Irrigation Planter Works

Think of how water moves up a sponge. Or put a piece of paper towel in water and watch the water move upwards.

The same thing happens in a self-watering planter.

The water that's stored in the reservoir moves up through the soil.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Plants That Thrive in Sub-Irrigated Planters

Annual vegetable and herb crops do well in sub-irrigation planters.

Avoid plants that are susceptible to root rot when overwatered. (For example, I grow potted lemon trees, and they hate “wet feet,” soil that says consistently wet. Read more about potted lemon trees.)

Potting Soil for Sub-Irrigated Planters

Choose a potting soil with good wicking properties. Do not use garden top soil or sand.

Sometimes this is easier said than done...because you won't find "wicking" on potting soil labels.

(A bargain isn't always a bargain when it comes to potting soil. If you see discounted bags at big-box retailers, be wary.)

The large compressed bales of potting mix made for commercial growers have a more consistently good quality. If in doubt, start with these.

If you're making your own peat-based potting mix, here’s an important point:

There are different qualities of peat. The darker peat from lower down in a bog is not as good at wicking as the lighter coloured, "blond" peat that comes from the top of a bog. Blond peat isn't always available at garden centres; you might need to go to an outlet that supplies commercial growers to find it.

Make Your Own Sub-Irrigated Planter

It's fairly simple to make your own self-watering planters.

Below is a series of pictures from a batch of planters I made for my garage rooftop garden.

The materials I used were inexpensive, and available at a hardware store:

Plastic storage bin

Weeping tile (4” bendable plastic drain used around the foundation of buildings…the term used for this seems to vary by region)

Dishwasher drain pipes

Landscape fabric

The tools needed to make these were:

Drill to make overflow hole

Saw or utility knife to cut the weeping tile and dishwasher drain pipe

Scissors to cut the landscape fabric

At the time I made these, I spent about $20 per planter, a fraction of what commercially available self-watering planters cost.

Making a Planter, Step by Step

Supplies to Make a Sub-Irrigated Planter

Plastic storage bin

Weeping tile (4” bendable plastic drain used around the foundation of buildings…the term used for this seems to vary by region)

Dishwasher drain pipes

Landscape fabric (not shown)

Weeping Tile with Fill Tube

Weeping tile coiled around the bottom of the bin.

A hole cut into the weeping tile with a utility knife allows a piece of dishwasher drain hose to be installed as a fill tube.

Landscape Fabric

The reservoir space created with the weeping tile is covered with landscape fabric so that potting soil doesn’t fill up the weeping tile.

Don’t Forget This!

Drill a drainage hole near the top of the weeping tile.

The hole shown here was too small…and was blocked by a piece of perlite, so i had to drill a bigger hole.

Recycled Items to Make a Self-Watering Planter

I've also made self-watering systems using materials from the recycling bin, or things we already had on hand.

Here are examples of items you can use:

For the Water-Tight Reservoir

Retrofitting a large plastic pot to make a sub-irrigated planter. The reservoir is made from old flower pots, which are covered with wire mesh. The wick (not shown) is fabric. The mesh is covered with landscape fabric so that the potting soil does not fill up the reservoir.

A water-tight container such as a pail

Or, a liner to make a water-tight area in a container with holes (for example, pond liner or construction plastic)

To Hold the Soil Above the Reservoir Area

Drainage pipe

Downspout extenders

Downspouts

Weeping tile

Upside-down flower pots

Landscape fabric, or old t-shirts

For a Fill Tube

Water bottles

Dishwasher drain hose

Pop bottles (“soda” bottles if you’re in the US)

PVC pipe

Retrofit Containers into a Sub-Irrigated Planter

A hypertufa planter with sub-irrigation.

You can retrofit any traditional pot into a sub-irrigation system…even if they have holes in them.

Use a liner to make a water-tight reservoir area at the bottom, and then create an overflow hole.

Planter Maintenance

Potting mixes lose structure over time as the organic matter decomposes. Plan to refresh the potting mix periodically. How often you need to do this depends on the mix, and the conditions. Pay especial attention to the soil in the lower area that acts as a wick.

If you're using a fabric wick, check it annually to see its condition. Fabrics made from natural fibres break down fairly quickly.

Sub-Irrigated Planter FAQ

How deep should a sub-irrigated planter be?

Making a sub-irrigated planter from a smaller, shallower planter. This is perfect for shallow-rooted crops such as leafy greens.

A soil depth of about 30cm (12") is usually lots. Remember, gravity is working against the wicking action...and when the soil is very deep the water doesn't wick all the way to the top.

The larger the plant you’re growing, the larger the volume of soil that you'll need. A smaller container with a 15 cm (6") soil depth can be fine for many smaller crops, such as leafy greens. If you're growing something that gets larger, for example bush-type tomatoes, a larger volume of soil is suitable. (That's why I used the storage bins in the example above. Along with determinate tomatoes, we use them for okra, peppers, and eggplant.)

Can I cover the soil on a self-watering planters?

Plastic mulch over the soil holds in moisture and deters squirrels from digging up transplants in the spring.

Yes. A plastic mulch holds in moisture and stops weed seeds from germinating. There are biodegradable plastic mulches that last for a single growing season.

Lay the mulch over the potting mix, and then tuck it in tight at the sides. Once it's snug, you can cut and X in it with a sharp knife, and then plant into the X.

A springtime challenge for us is squirrels digging up newly transplanted seedlings from our planters. A simple solution is the plastic mulch, which seems to deter digging. (Soil is out of sight, and it’s out of their wee little squirrel minds.)

Or, if you don't like the look of the plastic, burlap works well too. (It's a natural fibre, so doesn't hold in as much moisture, but it deters digging and reduces growth of weed seeds.)

What about watering plants in a SIP from above?

This is fine. It will keep the soil surface moister, so there's more chance of weed seeds germinating. But there's nothing wrong with this...other than it can be much slower than filling using a fill tube.

Can I reuse the soil in my self-watering planter?

Over time, as the organic materials in soil break down, potting soil loses its structure. When is has less structure (fewer bigger particles and fewer air pores) it doesn’t wick as well.

So for best wicking, fresh potting mix work best.

But...replacing potting mix every year is both wasteful and expensive. I usually mix in some new soil mix every year, about 20 per cent.

What is an Earthbox?

It is a well-known brand of sub-irrigated planters.

Is a “global bucket” a sub-irrigated planter?

Yes. I suggest you search online to find out more about this easy-to-make pail-in-pail SIP planter that has a reservoir.

What is a wicking bed?

With a wicking bed, we're taking the same ideas we use in a sub-irrigated planter—just on a larger scale. Now we’re talking about a raised bed. A wicking bed has a water reservoir, fill tube, and overflow just like a SIP does.

If you’re researching wicking beds, you’ll see that the names SIP and wicking bed are often used interchangeably. For me, if it’s a moveable planter, it’s a SIP. If it’s a permanent bed, it’s a wicking bed. But don’t sweat the lingo—as long as you understand how it works inside.

Find out more about wicking beds.

Are there any things to watch for with SIPS?

Yes, salt build-up. Normally, excess salts that can accumulate near the soil surface wash away with watering, and then drain from the bottom of a container. But with a SIP, we’re not washing down salts with water, and any runoff is captured.

That means it's a good practice to flush out your SIPs in the spring. Water heavily from the top, enough to cause lots of water to drain through the overflow holes and carry away excess salts.

How can I automate watering in my self-watering planter?

An irrigation spaghetti tube goes into the fill tube on the SIP.

You can set it up with automatic irrigation that refills the reservoirs.

You want what’s called “spaghetti tubes,” small tubes that run from an irrigation line. One tube goes to each planter. (This sort of system is often used to irrigate container gardens, with “drip emitters” at the end of each spaghetti tube to regulate how much water comes out and onto the soil surface in the container.)

But when you’re setting up spaghetti tubes and drip emitters for a SIP garden, just put the tube and drip emitter right into your fill tube, so that when you turn on the irrigation, you’re replenishing the water in the reservoir—not wetting the soil surface. (That way, less water is lost to evaporation, and you’re not creating conditions suited to weed-seed germination.)

Experience will teach you how long to leave on the water supply to fill up the reservoir.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More on Growing Vegetables

Articles and Interviews

Course

Get great ideas for your edible garden in Edible Garden Makeover. Planning. Design. Crops. How-to.

25 Storage Crops to Help You Plan a Vegetable Garden that Feeds You Year-Round

25 storage crop ideas so you can plan a vegetable garden that supplies you with food year-round, even in cold climates, even if you don’t have a greenhouse.

By Steven Biggs

Plan a Vegetable Garden that Includes Storage Crops

I have a plan to turn a room in my basement into a proper root cellar. Braids of onions hanging from the ceiling, homegrown squash on shelves, lots of root vegetables…

But I don’t have a root cellar at the moment.

Maybe it’s the same for you.

The good news is that you can store a lot of homegrown food even if you don’t have a root cellar.

And having lots of vegetables to store starts with your vegetable garden planning. Choose crops that you can store in the garden. And choose crops that store well in protected areas other than a root cellar.

This articles helps you plan a vegetable garden with storage crops in mind.

Storing Crops

Pin this post!

I like to think of crop storage two ways. I recommend a bit of each in your vegetable garden plan.

In-Garden Storage: Leave cold-tolerant crops in the garden to continue harvesting as the growing season wraps up.

Harvest and Store: Harvest crops and store in a protected space.

In-Garden Storage

When cool weather arrives, some plants pack it in and die. Think of basil…a little sniff of cold and it drops its leaves in protest.

But some crops do very well in cool temperatures. They soldier on even as fall frosts arrives.

Even with these cold-tolerant crops, growth slows down and stops as days get shorter and shorter. But you can continue harvesting what’s there.

Leafy Greens for In-Garden Storage

Here are my favourite leafy crops for in-garden storage. And to be clear, I’m not suggesting that I harvest any of these winter-long here in Toronto. I don’t. But they have good cold tolerance, and I’ve often picked them from under a dusting of snow.

(If you want to take you year-round harvesting to another level, think of using a combination of cold frames and cold-tolerant crops.)

Kale is very cold-tolerant. If you can only grow one cold-tolerant green, start with kale.

Kale. For cold-climate gardeners, kale is a great season extender. It’s very freeze tolerant. It keeps going as light frosts arrive in the fall. Then as things freeze hard, it still hangs on. I’ve sometimes picked kale in January from under the snow. (The winter-harvested leaves are a far cry from tender, baby kale, by the way. But if you cook it accordingly, it’s a great homegrown addition to the menu.)

Celery. Reliable until hard freezes arrive. (And if you’re thinking celery isn’t a leafy green, you’re right. Except my favourite type of celery is “leaf” celery. Leaf celery, as the name suggests, is more leaf, less stalk—and it’s far less demanding and easier to grow than regular celery.)

Chard. Reliable through those first fall frosts, until hard freezes arrive. Chard also looks great, so if you’re interested in edible ornamental gardens, consider this as you plan your vegetable garden. (Maybe you have ornamental beds that would benefit from a pop of fall colour from one of the many colourful chard varieties.)

Parsley. Reliable until hard freezes arrive. Like chard, also a great ornamental plant. Use it as edging alongside annuals somewhere near your house, so that during muddy fall weather, it’s easy to quickly grab a few sprigs for supper.

Parsley stands up nicely to fall frosts.

A Couple More In-Garden Storage Crops

Keep harvesting cardoon until there’s a hard freeze.

Leek. Like kale, a plant you can keep harvesting into winter. And when there’s a mid-winter thaw, you can go get some more. The leaf tips begin to brown mid-winter…but that’s fine because it’s the lower portion we eat.

Cardoon. Cardoon keeps going through light frosts. It’s leaves wilt, and then spring back up as the day warms. (If you haven’t grown cardoon before, remember to blanch it or it’s horrid…my first forays into cooking cardoon didn’t win me any favours with my family!)

In-Garden Storage Using Straw Bales

As fall frosts arrive, there’s no rush to harvest many of the in-ground root crops. Carrots and parsnips are improved by frost.

A simple way to extend the time you can leave them in the ground is to place a straw bale over top of them. It insulates them and the ground below.

With a heavy mulch, you can leave carrots and parsnips in the ground until the soil freezes solid. Where I am, that’s midwinter. And the longer they’re in the ground, the better they last.

One more thought on leaving roots crops in the garden late: Remember that while carrots and parsnips usually grow under the soil and protected from the first freezes, beet roots often shoulder their way above the soil surface. Those exposed shoulders are quicker to freeze…and that affects the quality.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Harvest-and-Store

First things first: A root cellar is nice…but if you don’t have one, there are other ways to successfully store your harvest. Think about your storage options now, as you plan a vegetable garden. That way you can plant accordingly.

Here are different places you might be able to store your harvest:

Swiss chard with some frost on it. It will spring back up once the sun comes out.

Garage. My garage doesn’t freeze, so I use it to store root crops (and apples that I buy by the bushel…great way to save money). My garage stays just above freezing, and is fairly humid, making is well suited to storing produce.

Clamp. This is a traditional way or insulating harvested root vegetables outdoors, using soil and straw.

Cooler area in a heated basement. I have a room in my basement where I shut off the heat vents. It’s cooler (and darker) than the rest of the house. It’s not as humid or cool as a proper root cellar, but is excellent to store winter squash, garlic, and onions.

Unheated basement. A friend had an unheated basement with an earthen floor…perfect for stored crops!

Sunroom. If you have a sunroom that stays just above freezing through the winter, I’d be thinking about food storage…

Breezeway. Some houses have a minimally heated breezeway between the house and garage. It’s just calling out for food storage!

Attic. If you have an accessible attic, another option for cool storage! The logistics of carrying food up to an attic aren’t ideal, but if it’s all you have, worth a try.

Successfully Storing Crops

Storing crops in the right conditions can really extend the storage life.

Root crops can go into perforated plastic bags, or into moist sand or sawdust in crates. This prevents them from drying out.

Newspaper comes in handy too: cover trays of green tomatoes with a sheet of newspaper; and wrap cabbages in a sheet of newspaper.

Only store unblemished produce. If you have crops that aren’t good enough to store, cook them up or freeze them.

Harvest-and-Store Crops

Dry Bean

When the pods turn light brown, just pull up the entire plant to hang upside-down under cover to dry further. Great storage crop for long-term storage.

Beet

Leave a half inch of stem on the roots as you prepare to store beets. Then they won’t “bleed” as much. Look for varieties recommended for storage. A favourite of mine over the years has been ‘Cylindrda.’

My favourite storage crop! (I make beet borsch with some of mine every year.)

Cabbage

Not a crop that lasts all winter in a root cellar, but you can keep it for a couple of months. The outer leaves dry, and you’ll peel those off as you prep the cabbage for use in the kitchen.

Use midsummer transplants to grow cabbages for winter storage. Harvest as late as possible for storage.

(Don’t forget that you can also use some cabbage to make sauerkraut. Find out how to make your own sauerkraut.)

Cabbage, along with other cole crops such as broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts are also excellent for in-garden storage as they keep going through early fall frosts.

Carrot

Use midsummer transplants to grow cabbages for winter storage. Harvest as late as possible for storage.

Sweeter after some frost. Look for varieties recommended for storage. ‘Bolero’ is a variety that I like for storage.

Cerleriac (a.k.a. celery root)

Often overlooked, and a great addition for gardeners growing for storage.

Garlic

Easy to grow lots in a small space, and easy to store for gardeners without many storage options, because it and onions like things dryer than the root crops.

Horseradish

As you’re planning your vegetable garden, remember that this is a deep-rooted perennial. So pick a permanent spot for it.

Jerusalem artichoke

A somewhat invasive perennial, so pick a permanent spot for it.

Onion

Braided onions drying before going into storage.

Store onions after curing. Like garlic, important to dry and cure for a couple of weeks before storage. If not properly cured, doesn’t last as long.

You don’t have to braid onions. Another way to store them is to hang them in a mesh bag—so there is good air circulation around the onions.

Parsnip

Sweeter after they go through some frost.

(One year I grew far too many parsnips, and had the brilliant idea of making parsnip wine. Alas, it was horrid…couldn’t even use it as cooking wine.)

Peppers

Often overlooked, but smaller, thin-skinned pepper varieties are easy to dry. Once dry, you can hang them in your storage area, where there’s good air circulation.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Potato

Plan for your storage potatoes to be ready late in the season. During the summer, storage spaces aren’t usually as cool as they are in the fall—so your potatoes can sprout quickly when stored too early.

Don’t put early potato harvests into storage. Plan for a later harvest for storage.

Radish (winter)

So often overlooked, and a great addition in a storage-focused garden.

Root Parsley

Ditto above.

Rutabaga

My mother-in-law’s must-have cooked veg at the Thanksgiving table!

Squash

Pick before light frosts for best storability.

Tomato (keeper)

Keeper tomatoes in the spring.

It’s easy to overlook tomatoes as a storage crop, but there are thick-skinned tomato varieties that can last until spring! They’re called “keeper” or winter tomatoes or storage tomatoes.

These aren’t great for tomato sauce, but are nice chopped into a salad or bruschetta.

Find out about keeper tomatoes.

Find out my top tips for starting tomato seeds indoors.

Get ideas for different ways to stake tomatoes.

Learn about ripening green tomatoes indoors.

Turnip

A quick-to-mature crop. Remember, the greens are edible too!

Watermelon

Watermelons last a month or so, a nice treat to stow away for a snowy day!

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Want Green Veg Over the Winter?

Find out how to grow microgreens indoors.

Need More Ideas to Plan a Vegetable Garden?

Articles and Interviews

Hear an agronomist share top tips for winter vegetable gardening.

7 Vegetable Garden Layout Ideas To Grow More Food In Less Space

Courses on Edible Gardening

Force Rhubarb Indoors

Force rhubarb indoors and harvest tender, pink rhubarb mid-winter while the snow flies outdoors.

By Steven Biggs

Force Rhubarb Indoors for a Mid-Winter Harvest

Rhubarb and candles?

One day I got chatting with my neighbour’s fence installer, who was interested in my garden.

I was picking rhubarb as we spoke, so I mentioned that I also force rhubarb in my basement over the winter.

That’s what got us on the topic of candles.

He was from Yorkshire, England, an area that once produced 90 per cent of the world’s forced rhubarb. He explained that the tradition there is to tend and harvest the crop, grown in big, dark sheds, by candlelight.

After we chatted I went online to see pictures of Yorkshire forced rhubarb. It’s beautiful! The long stems are bright red, and they’re topped with small yellow leaves. Farmers grow this forced rhubarb in the dark to get very long, tender stems. A small amount of light can change the way the rhubarb grows, but because the candles give a faint light, they don’t affect growth.

It’s easy for home gardeners to force rhubarb over the winter too. (You can opt out of using a candle if its’ not your style! I don’t use one.)

My winter-forced rhubarb. Not quite as nice as what they grow in Yorkshire, but still a nice winter treat.

How Forcing Rhubarb Works

Let’s back up to get a handle on what we’re doing. When we force rhubarb indoors over the winter, we’re tricking a dormant rhubarb root into thinking it’s spring.

We trick it by putting it somewhere warm.

That warmth stimulates growth.

If you’ve ever grown plants in conditions where there’s not enough light, you’ll know that they get lanky, with long stems.

The rhubarb sends up long stems too, and the leaves stay quite small while there’s no light.

If there’s light, upward growth slows, and stems and leaves develop a green colour from photosynthesis. It doesn’t take a lot of light to change the growth. Hence the candles.

Rhubarb grown in the garden is more green and fibrous than forced rhubarb.

Why Force Rhubarb Indoors

What makes forced rhubarb special is that by excluding light, we get very long, tender stalks with a sweeter, milder flavour than rhubarb grown in the garden.

(Intrigued by the idea of excluding light to change quality? Here’s a fun article about blanching veg.)

Forced and outdoor-grown rhubarb are two very different things. The former has a delicate flavour and beautiful colour. The latter is greener and more fibrous.

Fresh forced rhubarb is a nice addition to the menu over the winter.

There’s one other reason to consider forcing your own rhubarb: It fits in nicely with rhubarb patch care.

In the right location, a patch of rhubarb grows larger each year. When a clump of rhubarb is well established and thriving, you simply “harvest” some of it in the fall by dividing the clump once the leaves have died back and it is dormant. Like plants in a perennial flower garden, dividing and bringing in fresh soil and compost is a good practice to keep a rhubarb patch thriving. As you divide the rhubarb patch, keep the hunk of root that you dig out for forcing.

Steps to Forcing Rhubarb Indoors

In the Summer

When conditions are good, a rhubarb patch gets larger every year. Don’t dig anything yet, but select a part of your patch that you can “harvest” for indoor forcing once the patch is dormant in the fall.

In the Fall

When you divide your clump of rhubarb in the fall, you get roots that you can force indoors over the winter.

The rhubarb should be dormant before you dig out a piece for winter forcing. Wait until the leaves have died back before digging. (But do it before the ground freezes!)

Then harvest the part of your rhubarb patch that you chose during the summer. Rhubarb crowns are woody, so you’ll need a spade to chop down into it.

Pot up the dormant root. Some years I pot the roots into recycling bins. Some years into large black nursery pots. Crates might work well too. Just like a houseplant, you want excess water to be able to drain from the bottom. (Also think about what to put underneath the potted rhubarb root if you don’t want water on the basement floor.)

Once the rhubarb root is potted up, store it somewhere cool until it’s time to force it. I put mine in my garage until mid-winter, when I’m ready to bring it in the house to force it. The roots are very cold tolerant, so if your storage area freezes, that’s fine.

There’s no rush to bring the dormant rhubarb root indoors. Let the root remain dormant and at a cool temperature for a few weeks.

Where to Force Rhubarb Indoors

In a previous house I forced rhubarb in the cold cellar under the stairs.

The rhubarb will grow when it is placed somewhere warm. Remember, you’re simply tricking the plant—making it think spring has arrived.

In a previous house, I put the rhubarb in a dark cold cellar under the stairs.

In my current house, I put the rhubarb in my furnace room.

Taking Care of Forced Rhubarb

Care is simple: Just water the soil as it starts to get dry. It should be moist, not wet.

Don’t feed the plant. It is using energy stored in the thick, fleshy roots.

Supplies to Force Rhubarb Indoors

A container to pot up the dormant rhubarb root

Potting soil

Candle (optional!)

Harvesting Forced Rhubarb

Harvest stalks when long enough to use. How big they get will depend on how much root you dug out, and how much energy was stored in that root.

Repeat a few times.

You’ll find that the longer you leave the forced rhubarb root to produce stalks in the dark, the skinnier and skinnier the stalks become. That’s because as the plant continues to send up stalks in the dark, it’s using up its stored energy.

(I find I get about three harvests before stem size gets too skinny to make it worthwhile harvesting.)

When you find the stalks are very skinny and no longer worth harvesting, you can move the plant to the light to just let it grow. Or, if you don’t have space, put it back into your cold-storage space until spring.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Force Rhubarb Outdoors

By the time spring arrives, your winter-forced rhubarb root will be done producing rhubarb.

But you can also force some of your in-ground rhubarb plants. Again, it’s a combination of darkness and extra heat that gives you long, tender stalks.

You do this spring forcing right in the patch, without disturbing the plant.

Here’s what to do:

A rhubarb forcer, a purpose-made terracotta pot with a removeable lid for forcing rhubarb.

As you see buds start to swell on the crown, cover a part of the patch with a large inverted pot or garbage can. (To exclude the light and get nice, pink stalks, cover the drainage holes of the pot to keep out light)

You can insulate the sides of pots with leaves or straw if you want to speed up the process by making it warmer inside

Pick once the stalks reach the top of the pot

Give the roots you forced “time off” over the summer to recharge – don’t pick from them

There are also purpose-made terracotta rhubarb forcing pots. They’re beautiful, but I’ve never seen them for sale here in Ontario. And I suspect that if I found them, they’d cost and arm and a leg.

Supplies to Force Rhubarb Outdoors

Healthy, established rhubarb plant

Large pot

Tape to cover holes in the pot

Straw or leaves to insulate the outside of the pot

Rhubarb Forcing FAQ

What if my indoor forcing area has some light in it?

If there is enough light, you will not get the elongated, bright red stalks. Instead the plant will produce more compact stalks with some green chlorophyll in them. Not the end of the world…but you can get green stalks all summer. So create a dark space using a curtain or tarp.

Why are my forced rhubarb stalks smaller than the ones I see at the grocery store?

Commercial growers will often let rhubarb plants grow two or three years without harvesting any stalks before using the root for forcing. That means the root has a lot of stored up energy. In a small home garden, where the gardener is forcing roots that have been harvested from, there won’t be as much stored energy.

What should I do with the rhubarb plant after forcing?

Commercial growers often discard roots that they’ve forced. But you can plant the spent rhubarb root in your garden or share it with a neighbour. But don’t harvest from it for a couple years – allow the plant to recover and store energy.

I just planted my rhubarb. Can I force it?

No. There won’t be enough stored energy in the root to give you good results…and if it’s a small plant, you might kill it. Commercial growers often grow plants in the field without harvesting anything for two or three years to allow the plants to store up energy before forcing.

What about bugs?

Because the potted roots were harvested in cold temperatures, and then stored somewhere cold, don’t worry about bugs.

What’s a rhubarb stick?

Some people refer to rhubarb stalks as “sticks.”

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More on Rhubarb

Ontario Farmer Brian French forces 10,000 square feet of rhubarb over the winter.

Hear how he forces rhubarb, and find out his rhubarb-growing tips.

Want More Ideas?

Guide to Blanching in the Vegetable Garden

How to Blanch Celery, Cauliflower, and Other Vegetables. Blanching in the garden refers to covering up part of all of a plant to exclude light.

By Steven Biggs

How to Blanch Celery, Cauliflower, and Other Vegetables

One word, two meanings!

For many people, blanching vegetables means a quick dip in boiling water before freezing them. This type of blanching slows down or stops the enzymes that cause colour and flavour loss.

But there’s another type of blanching, and it’s something that we do right in the garden.

Blanching in the garden refers to covering up part of all of a plant to exclude light. Without light, it grows differently.

The result is a milder tasting and more tender crop.

Keep reading to find out what crops you can blanch—and how to do it.

Common Crops

These are crops that are commonly blanched in the garden. You can grow them without blanching, but blanching improves the quality.

Asparagus

Cardoon

Cauliflower

Celery

Endive and Escarole

Leek

Rhubarb

Different Ways to Blanch

Soil hilled up along a row of leek plants.

Depending on what you’re growing, and how you want to grow it, there are a few ways to blanch vegetables in the garden.

Remember, blanching just means excluding sunlight. Here are some ways to do it:

Cover the plant (e.g. inverted pots)

Hill the plant with soil

Wrap something around the plant (e.g. cardboard or newspaper)

How Long?

The plants are blanched for a few days to weeks before harvest – not the entire life of the plant.

Crop Blanching Tips

Asparagus

If you’ve ever seen white asparagus, these are spears that have been blanched by hilling with soil. It’s a delicacy in Europe, less common in North America.

Cardoon

Blanching cardoon plants by wrapping them in fabric.

I’ve heard of people growing cardoon in a trench…but it’s a pretty big plant needing a pretty big trench. Instead, wrap mature plants 2-3 weeks before harvest, leaving the top of the older leaves exposed, but the base covered. The idea is that the inner leaves are white and tender. Some people use cardboard, but I think the most elegant cardoon blanching I’ve seen was burlap coffee sacks.

Cauliflower

With cauliflower we blanch the head. White-headed cauliflower is blanched to keep it bright white. It is still edible if you don’t blanch it…but can develop a yellow or green tinge, and get a stronger flavour.

Blanching cauliflower by tying together leaves to cover the head.

As the developing heads begin to expand, tie leaves around them to keep out the light. Don’t wrap the leaves too tightly over the small head as it will need space to expand. I’ve heard of people using paper bags, but if there are leaves there, it’s easier and less wasteful.

There are also “self-blanching” types of cauliflower, with leaves that naturally grow around the developing head. Some of these varieties still benefit from additional wrapping.

Celery

With celery we blanch stalks for 2-3 weeks leading up to harvest, keeping the leaves at the top exposed. Blanching helps reduce bitterness and lighten the stalk colour.

Blanching celery with waxed milk cartons that have the top and bottom cut out.

As with cauliflower, there are also “self-blanching” celery types. These have a lighter colour and milder flavour.

Hilling soil around the stalks is one way to blanch celery. Grow celery in a trench, and then gradually fill in the trench with soil leading up to harvest. If you use soil, first wrap the stalks with newspaper, so you don’t get lots of soil between the stalks.

You can also blanch celery by tying paper around the stalks, covering with waxed cardboard milk cartons or tall narrow tins that have both ends removed, or surround the stalks with boards.

Blanching celery plants with boards.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Endive and Escarole

A board propped up over a row of endive or escarole is an easy way to blanch it.

Many people grow endive and escarole for the bitter taste. But you can blanch them to reduce the bitterness. Cover entire plants for a week before harvesting.

For individual plants, cover with a clay pot or a paper bag. For a whole row of plants, place a board over the row.

Leek

The base of leek plants can be blanched to give tender white flesh. In late summer, hill the base of the plant with soil, or wrap to exclude light. As with celery, leeks can also be grown in a trench that is gradually filled in as the plant gets taller.

Rhubarb

Blanch rhubarb by cover up plants with an inverted bushel basket as they begin to grow in spring.

When rhubarb is blanched it produces tender, elongated stalks that have a bright pink-red colour.

To blanch rhubarb, put an inverted bushel basket over the plant in the spring, as it begins to grow.

Why Not Blanche a Weed!

While a weed for many, dandelions are a kitchen staple for others. Our springtime menu includes dandelion frittata or a mixed salad with dandelion leaf pieces.

But dandelion, like its kin in the chicory clan, can be very bitter. The solution is to blanch dandelion. Simply cover with an inverted clay pot or a board – and you’ll be rewarded with tender, translucent, and mild-tasting leaves.

Blanching Challenges

Blanch dandelion by covering with an inverted pot or a board.

Blanching is easy to do. The biggest challenge is remembering to do it in time.

Another challenge is lightweight covers that blow away on windy days. If you use terracotta pots, they’re heavy enough to stay in place. But plastic coverings can blow away. The solution is to weigh them down with a brick or rock.

Top Blanching Tip

Put a note on your calendar to remind you to blanch your crops ahead of time.

Garden Blanching FAQ

Is Blanching Optional?

You don’t have to blanch these vegetables to eat them. But blanching gives a milder tasting, more tender, and more attractive vegetable.

What is “Self-Blanching?”

Some varieties don’t need help from gardeners with blanching. For example, with cauliflower, self-blanching varieties have leaves that grow to cover the head. Self-blanching celery has stalks with a mild flavour that don’t require blanching.

Why Grow Varieties that are not Self-Blanching?

You might be wondering why bother growing varieties that need blanching when self-blanching varieties are available. As you choose varieties, self-blanching is one trait to consider, along with other things such as having different harvest windows, price, and availability.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Looking for More Ideas?

Gardening Courses

Grow Vegetables in Straw Bales

Straw bale vegetable gardening is an easy way to create more growing space.

By Steven Biggs

Make More Growing Space with Straw Bale Gardens

I started straw bale gardening to solve a problem.

The problem? We needed more growing space for my daughter Emma’s 100-plus tomato varieties.

We have a big yard for the city. But there’s a black walnut tree that makes much of the yard unsuited to growing tomatoes.

(That’s because black walnuts give off a compound that kills the tomato plants…and a number of other plants too.)

With a long and ugly driveway that could fit a couple of school buses, Emma and I began to imagine a tomato plantation on the driveway.

In this post I’ll talk about how to use straw bales to make gardens on paved areas or over soil that’s not great for gardening.

Straw Bale Driveway Garden

Straw bales are an easy way to create a near-instant garden on paved surfaces and areas with poor soil. That’s because the straw bale is both the growing medium and the container.

Here’s how it works: As the straw bale decomposes, it creates an ideal growing medium that is well aerated and holds lots of moisture. It’s like a big sponge. It’s perfect for plant roots – better than many garden and container soils.

In short, you’re composting a bale of straw, and growing your vegetable plants in it at the same time.

Straw Bale Gardening: Top Tip

Our straw bale driveway garden

The most important thing to remember is that bales should be “conditioned” before you grow in them.

Conditioning means kick starting the microbial action. And you know when it’s working because as the microbes start to break down the straw, the temperature inside the bale goes up. We don’t plant in it yet…it might be too warm for our plants.

As the temperature comes down, your bale is ready to plant. Some people use a thermometer. I stick in my finger. It’s not an exact thing.

I allow 3-4 weeks for this conditioning process. It might be less if you’re somewhere warmer than me.

Since the bales in our driveway garden are for heat-loving tomato plants that we put out in late May, we start conditioning the bales late-April to make sure they’re ready for the planting date. I just work back four weeks from my planting date.

Straw Bale Garden Setup

Emma conditioning the newly arrived straw bales.

Before your bales become heavy from watering them, it’s a good time to think about how you want to arrange them. There’s no right or wrong, it depends on your situation:

If you’re planning to use a long soaker hose, you might want them in a long line.

If you’re gardening with kids, arranging them in a square makes for a nice hidoute once the plants get bigger

If you’re watering with a hose, arrange the bales so you can easily move amongst the bales with the hose

How to Orient Straw Bales

Once you know how you want to arrange the bales, think about how you’re orienting them. You can place them so that the loops of twine are on the top and bottom – or the twine is at the sides. Both ways of orienting the bales are fine.

But here’s how I do it: When positioned so that the twine is at the sides, the straw within is mainly oriented vertically. Bales positioned this way absorb more water, so it’s less likely to run off of the side of the bale.

How to Condition Straw Bales

To condition the bales – which just means getting the microbes working – we need 2 things:

Water

Nitrogen

In this picture the bales are oriented with the twine at the top and bottom of the bales. We now prefer to have the twine at the side for easier water penetration.

Place a nitrogen source on top of the bales and water well. The goal is for the water to soak into the bale and move some of the nitrogen into the bale. Use a low pressure and volume so that water doesn’t flow over the sides of the bale (and take the nitrogen with it).

More on the nitrogen source: When you’re looking at the numbers in the fertilizer formulation, you want the first number, the nitrogen, to be higher than the others. For example, blood meal is 12-0-0. That’s what I usually use.

Other years I’ve also used a high-nitrogen organic fertilizer derived from guano, and a lawn fertilizer.

Here’s how I condition straw bales with blood meal:

I water well every day for the first week.

Starting on the first day, and again every other day, I put a 2 cups of blood meal on the bale BEFORE watering (so the water moves some of the blood meal into the bale).

I give 3 applications of blood meal.

As we get into week 2, the bale should be warming up nicely inside!

After 2 weeks, fertilize the bales with a balanced, all-purpose fertilizer.

During this conditioning process, the temperature can go up to about 50°C (120°F), and then it drops. You can plant in the straw bales once the temperature has dropped below about 26°C (80°F).

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Straw-bale Garden Plant Layout

Plant densely to make the best use of space in your straw bale garden.

Wondering about plant spacing in a straw-bale garden? Because a well-managed straw bale garden provides plants lots of moisture and an excellent growing medium, you can plant densely.

We aim for two or three tomato plants per bale. Around those tomatoes we sow bush beans and leafy greens.

Something else to think about with straw bales is that you can plant into the side of the bale too. We’ve grown dwarf tomato plants out the side of bales, while at the top are normal determinate and indeterminate varieties.

How to Support Plants in Straw Bale Gardens

Because there is a paved surface below, and because the bales decompose and start to collapse over the summer, regular staking is not an option.

Here’s what I do instead of staking:

Use 3-4 stakes positioned over the bale to create a self-supporting tee-pee.

Put the bales next to a fence and grow vining crops up the fence.

Looking for tomato-staking ideas? Find out how to stake and support tomato plants.

Straw Bale Garden Planting and Care

How to Plant in Straw Bales

When I show pictures of straw bale gardens to groups, I’m asked where the soil is. There doesn’t have to be soil, because the straw is the growing medium.

When transplanting, use a trowel to pry an opening into the bale. Then place the transplant into the opening, and close up the opening. Be sure to cover the transplant roots with straw so they remain moist.

With large seeds like beans, we just insert them right into the bale. Again, no soil necessary.

When direct seeding smaller seeds onto a straw bale, a thin layer of soil is helpful. We add about an inch of soil over the top of the bale if we’re seeding leafy greens. Use a potting soil or good garden soil that won’t cake with frequent watering.

Straw Bale Garden Fertilizer and Water

Once your bales are conditioned and planted, feed with a balanced, all-purpose feed and keep them well watered. Because the inside of the bale remains well aerated, excess water is not likely to harm the plants. But excess water will wash away nutrients.

If there are not many bales in your garden, hand watering might be fine.

For larger gardens, drip irrigation or a soaker hose works well. Position the soaker hose to sprays downwards, into the bale.

Grasses and Mushrooms on Straw Bales

It’s normal to get mushrooms growing on straw bales. It means you’ve created good growing condtions.

Don’t be surprised to see little grass-like plants and mushrooms growing on the bales. These are good – it means you’ve created good growing conditions.

The grasses are any residual grain within the bale that germinates and grows. They won’t out-compete your crops. Just pull them off.

Straw Bale FAQ

What do you do with Straw Bales After Harvest?

After a year of growing I use the straw to mulch gardens, on pathways, and in my compost pile.

How Many Years do Straw Bales Last?

I’ve sometimes used bales a second year. How fast a bale decomposes varies with your weather conditions. Friends in warmer areas report that one year is the maximum for them.

What if the Twine Breaks?

Broken bales? No problem. In this straw bale garden the tall sections are tomato cages filled with loose straw from broken bales.

If possible, tie it back together; or use a new, longer piece of twine to tie together the bale. If that doesn’t work, you can pack straw into a cage or pot instead.

As you carry the straw bales, try to do it in such a way that the twine does not slide off the side of the bale.

Do Straw Bales Leave Marks?

Yes. Straw bales can darken paved surfaces.

I don’t recommend using them on wood because it creates conditions that could speed up the decay of the wood.

One year I had them against a board fence, and it resulted in dark marks on the fence – so I now position the bales a couple of inches away from the fence.

What About Hay Bales?

Hay bales can also make an excellent growing medium, but there are a couple of reasons they’re not used as frequently as straw bales:

Hay often includes lots of grass seed – not something you want to introduce to your garden

Hay is often more expensive than straw

What are the Best Plants for the Straw-Bale Gardening method?

You can grow a wide range of vegetable crops in straw bales.

Heat-loving crops benefit from the warm root zone in the bales

Root crops develop very well in the well-aerated growing medium

Leafy greens grow well and can be planted underneath other crops such as tomatoes

Cascading plants such as nasturtiums (for edible flowers!) can drape down over the side of the bales

Where can I Buy Straw Bales?

Straw bales are fun for kids.

I used to bring home loads of bales in my minivan. And my family hated all the prickly little bits of straw it left everywhere. So now I just get straw delivered.

To find a farmer, use an online classified advertising website.

And if you have kids: Get straw bales earlier than you need them – for your kids. Straw bales are like giant, biodegradable Lego blocks.

Don’t Straw Bales attract Rats?

The mention of straw has some people wondering whether straw bale gardens will be overrun with rats.

It’s a good question. Not in my experience.

The thing to remember with rats and mice is that they’re looking for food, shelter, and water.

A bale on a paved surface doesn’t give them burrowing room. Doesn’t give them water. Doesn’t give them much food.

What’s more likely to attract rats is bird baths, bird feeders, leaving out pet food, and improperly stored garbage. (On that note, gardening itself, and growing plants with seeds and fruit that are food for rodents, attracts rats.) Remember too, that they’re already abundant in many areas – just not out and about at times that we see them.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More Vegetable Garden Techniques

Ornamental Vegetables for Fall

By Steven Biggs

Vegetable Crops That Look Great in the Fall

As I write this, it’s spring. But I’m picturing my fall garden.

I was just scouting out the spot where my Swiss chard will go this year.

I always fit in chard close to my kitchen window.

An Ornamental Edible

In the garden outside my kitchen window I weave together the ornamental and the edible. I especially treasure edible plants with ornamental appeal.

And that’s where chard fits in.

Swiss chard paints this part of my garden in yellows, reds, pink, and orange.

Summer-Long Production

Leafy greens like lettuce, spinach, and arugula come and go with summer heat.

They bolt

They get leathery

They get bitter

But Swiss chard sails through the heat with a prodigious output of tender leaves.

A Long-Lasting Edible

As cool, grey fall weather arrives, Swiss chard is a bright spot in a fading garden.

It shines.

When frost renders swathes of the garden a wilted green-brown, chard still shines. The bright leaves bow to the frost, then spring back up as sunshine warms them.

It perseveres until a hard freeze.

Put Chard Where You Can See it in the Fall

I’m picturing the spot where my chard will go, and making sure it’s somewhere I can enjoy looking at it from my kitchen window through the fall.

More Ornamental Vegetables for the Fall Garden

Cardoon is another ornamental vegetable that looks great in the fall. Find out more about cardoon.

Artichokes hold up nicely in fall weather. Find out how to grow artichoke.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Home Garden Soil Contamination

By Steven Biggs

Understanding the Risk of Soil Contamination Around Your Home

AFTER MOVING INTO MY WORLD WAR I-ERA HOUSE, I decided to find out if the paint-chip-studded soil next to the house was safe for growing edible crops.

Many pre-1991 paints contained lead, and those that are pre-1960s—particularly exterior paints—are thought to be the worst culprits.

Lead was also used as a gasoline additive into the 1990s. So urban areas with older buildings, where there have been years of car exhaust—and maybe even industrial emissions—tend to have higher soil lead levels than rural, agricultural areas.

With this in mind, I wanted to understand what, if any, risk lay hidden in my soil.

If you’ve wondered what, if anything, to check with the soil in your garden, keep reading for a practical way to approach soil contamination.

Conflicting Information

With an older house, I was worried about lead contamination from paint.

The more I delved into the question of urban soil contamination, the less clear the issue became.

I found a government fact sheet saying there was minimal risk to consuming veggies grown in soil with lead levels below 200 parts per million (ppm)

But one from another jurisdiction advising 300 ppm.

Both noted increased risk for children (think soil moving hand to mouth), in which case one gave a safe upper limit of 100 ppm.

I was left wondering whether I should go with 100, 200 or 300 ppm.

So I Got on the Phone

When I called Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment, I was told that contaminant levels in typical agricultural soil are often less than urban areas, but there should be no concern as long as the readings for my soil fell below the residential standards, as set out in the provincial Environmental Protection Act.

But…I should also keep in mind that a reading above that residential level isn’t necessarily unsafe.

Understanding soil contamination was starting to seem as fun as doing my tax return.

So, after scanning the Act, I added 45 ppm lead (for typical agricultural soil), 120 ppm lead (for residential standards), and a big question mark (for “isn’t necessarily unsafe”) to my growing list of values.

This was getting to be as much fun as preparing a tax return!

And just as filling in a tax return isn’t black and white—think of deciding what’s tax deductible and what’s not—I sensed balancing soil contamination and growing edibles had shades of grey, too.

So I set out to see how urban veggie growers can best tackle the question of soil contamination without being mired in conflicting numbers.

What Other Growers Do

Travis Kennedy, an agrologist involved in community garden projects, also raises produce at his Lactuca Micro Farm in Edmonton. “Pragmaculture,” he responds with a laugh, when I ask how he deals with possible soil contamination. His pragmatic approach to urban agriculture is to always use raised beds, bringing in soil he knows is safe, because he always assumes that there may be contamination.

Ward Teulon, also an agrologist, runs City Farm Boy in Vancouver, designing and building vegetable gardens. Teulon explains that sending backyard soil samples to a laboratory doesn’t always give a clear picture of what’s in the soil because urban soils are moved around a lot and are not uniform. He agrees, however, that interpreting results from expensive tests, which can cost hundreds of dollars, can be daunting. If there is a cause for concern, he believes money is better spent bringing in soil to make a raised bed. “Find out your property’s history,” he advises, because many urban soils are perfectly fine.

Luckily for me, my property’s history seems clear-cut, from agricultural to residential.